Writing a fast (mostly) Binox solver

We’re going to look at solving Binox puzzles in this post today. The game has also been known to go under the popular name Tic-tac Logic if you are familiar with that.

If you just want to try it, you can find that here.

What is the game?

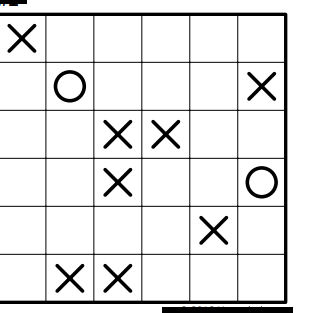

Binox is a binary game with a board looking like this:

The objective is to fill the entire board with either “X” or “O” given some rule scheme – which varies in difficulty. The rules are as follows:

-

No row or column may have more than three characters that are the same in a row. For example, this is illegal:

… since there is 3 of the same character in a row. However, something like ` XX00XO` is legal

-

No row or column may have an unequal amount of characters. This means the above image would also be illegal as well.

Corollary: The puzzles width and height must be even in length.

Proof: Suppose some board exists where n, the length of the board is odd. Let x be the number of characters assigned “X” in a complete board. Let y be the number of characters assigned “O” in a complete board. Given the restriction

x = yandx + y = nthen consider the following cases,xis odd,yis odd. The result of two odd numbers added together is always even.xis even,yis even. The result of two even numbers added together is always even.- Any other combination implies breaking the constraint

x = ysince a number cannot be even and odd at the same time.

-

Each row and column in the entire puzzle must be unique. This means you cannot repeat the same row or column anywhere.

With these restrictions, solving the puzzle becomes a bit more than just throwing random “X” and “O”s at the grid. Let’s look at an algorithm that can solve this.

The simplest thing that can solve this

I tried a few things that were “clever” and “complicated” such as generating permutations of rows and comparing to other possibilities for other rows. We won’t go over those – since it turns out the best solution I found is one of the simpler ones! You can read about general strategy on the web but the example I’m going to step through below is a general approach I came up with.

The algorithm is as follows:

- Let Q be the set of indices on the grid that still need to be found (that is, they are neither “X” or “O” yet; often denoted as blanks). Initialize this to all possibilities.

- Find an entry, any entry, that when you would place a

Xor0there (but not both! think… XOR) the following criteria is true:- The column and row associated with this entry does not contain a streak of 3

- Modifying this entry does not make it impossible in the future for other to-be-determined entries in that row or column to respect the rules. The main one to worry about is the quota surrounding equality. If

nis the row or column length, then by placing on this entry a specific token, the number of “X”s or “O”s must not exceedn/2since it would then be impossible for other to meet the criteria.

- Remove this entry from the set, since it is now placed

- Continue this process until all entries are placed

- If you at some point cannot find such an entry in the set, the puzzle has no solution.

Let’s break down why this is the case.

- Why XOR for choices? This one is pretty simple – if you have two choices and you can only make one of them without breaking the rules at any given step, then that choice is obvious. It’s the ideal scenario.

- Why the count guard? This is also pretty simple – if you let a row or column exceed the length divided by two – the others cannot meet the criteria of being a valid “slice” as explained above

- Wouldn’t we run out of things with only a single choice? As you place more entries, other entries become more obvious as to what they must be since the decisions of other entries from the set are now dictating their possibilities. Each choice made this way only enables more information for future moves – preventing you from ever barring off future choices for other moves.

Automating it all

Of course, this is easy to describe so we can encode it inside of an application. I won’t go over all the implementation details but you can describe the entire main algorithm like so, in Javascript:

class PuzzleSolutionSolver {

solve(board) {

let activeBoardPointer = board;

const pointsToSolveFor = activeBoardPointer.getIndiciePairsThatAreNotFilledIn();

let iterationsBeforeGivingUp = pointsToSolveFor.length;

const originalIterationsBeforeGivingUp = iterationsBeforeGivingUp;

while (pointsToSolveFor.length > 0) {

const pointToSolveFor = pointsToSolveFor.shift();

const theoryWithOne = this._isTheorySafe(activeBoardPointer, pointToSolveFor, '1');

const theoryWithZero = this._isTheorySafe(activeBoardPointer, pointToSolveFor, '0');

if (theoryWithOne ^ theoryWithZero) {

const tokenToProceedWith = theoryWithOne ? '1' : '0';

activeBoardPointer = activeBoardPointer.withPointChangedTo(

pointToSolveFor,

tokenToProceedWith

);

// Let it cycle around the list a few times. This could be dangerous in some cases since

// you might let things spin for a long time but this should only happen on VERY large boards. So it's not a huge deal

iterationsBeforeGivingUp = originalIterationsBeforeGivingUp;

} else {

// Both were doable, so we cannot make a choice since we are unsured yet

// so we place it back on the queue in hopes that something other mutation

pointsToSolveFor.push(pointToSolveFor);

iterationsBeforeGivingUp--;

}

if (iterationsBeforeGivingUp === 0) {

throw new Error(

'Reached the max iteration count. Could not converge on a solution. Giving up...'

);

}

}

return activeBoardPointer;

}

// helper functions

_isTheorySafe(board, point, token) {

board = board.withPointChangedTo(point, token);

const slices = board.getSlicesForPoint(point);

const horizontalSlice = slices[0];

const verticalSlice = slices[1];

const isMaintainingSliceQuotaIntegrity =

!horizontalSlice.isExceedingQuota() && !verticalSlice.isExceedingQuota();

const isMaintainingRunIntegrity =

horizontalSlice.isNotSlidingWindowLargerThanThree() &&

verticalSlice.isNotSlidingWindowLargerThanThree();

return isMaintainingRunIntegrity && isMaintainingSliceQuotaIntegrity;

}

}

You could even cut some of this down a bit as well. You can dig into the actual implementation of some of these rules in the full implementation on my Github. It’s a short read – the entire thing (with all the tests, which is most of the code) clocks in at less than 1000 lines of code. It should be easy to digest.

Let’s first examine the puzzle posed above.

| X | - | - | - | - | - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | O | - | - | - | X |

| - | - | X | X | - | - |

| - | - | X | - | - | O |

| - | - | - | - | X | - |

| - | X | X | - | - | - |

Using the above rules, we can then run the program and find:

console.log src/PuzzleSolutionSolver.js:26

Going to proceed to change 0 | 2 with 0

console.log src/PuzzleSolutionSolver.js:26

Going to proceed to change 1 | 2 with 0

console.log src/PuzzleSolutionSolver.js:26

Going to proceed to change 1 | 3 with X

console.log src/PuzzleSolutionSolver.js:26

Going to proceed to change 2 | 1 with 0

...

If we step through these picks, we can see the rationale.

- If you were to add a “X” in that spot, there would be more X’s than allowed (since you could never possibly 4 O’s there). Therefore, the only logical placement is to put a “O” there.

- The same rationale for a row below – you can fill it in immediately.

- This has to be an “X” since otherwise, you would have 3 “O”s in a row. This is because the item to the left was filled in from the previous iteration, as we knew what it had to be

- You can’t have a streak of 3 – no prior info is needed since those “X”s are static and already placed.

… and there are more iterations. The number of choices grows smaller with each pick so the queue grows smaller until it reaches zero. There are more boards it has been tested on; you can check them out in the tests. I have some plans to add more tests from the PDFs provided. However, I tried to do a couple “cURLS” to get the PDFs and stopped being able to access the author’s site from home. Huh.

I’ve probably been blocked. Not sure why.

Further Optimization

Some heuristics could be developed to pick the points to prevent cycling through the list to find a valid one. For example, in the case of “exceeding quota” in a specific column and “forcing” a single token such as in example #1 and #2 above, we could have easily filled in the entire column. The solver began to do this but once it reached another point it could solve it just did that one first instead. The current implementation just uses a dequeue and pushes things to the back if i t can’t find something it can place immediately.

There’s probably other speed improvements to be made too: like not writing this in Javascript. But the solver runs so fast, already even with larger boards that I’m not that motivated to do much else. It was a fun afternoon project – now it’s time to say goodbye for now.

Thanks for reading.