Experimentation with Reverse Engineering - Trails in the Sky (FC / SC) Extracting Sprite Data w/ Unix Tools & Kaitai Struct

I recently began and finished the great Trails in the Sky series and was amazed at some of the technical skill that was used in such an old game (developed originally in 2001) and remastered for the English release. At the same time, I was interested in the internals of reverse engineering and how such things were performed. After reading an article I found on Reddit that covered the process of decompiling a Japanese visual novel game, I decided that now would be as good of a time as ever to give it a try.

The below post chronicles what I had to do to get it prepared for examination, including unpacking and my thoughts while reverse-engineering the file format(s) provided by the game. I’ll be doing this all on Arch Linux with the aid of a Windows VM for limited functionality but you all the information here should be applicable on any UNIX system and most of it should apply to Windows with some substitution.

Examining the game folder and the data files within

The first thing we should do when examining a piece of software we want to decompile is to see what we have to work with and what seems interesting. I’m going to work with Trails in the Sky (FC) in this case but the sequel shares a lot of traits it would seem. After installing the game from the Steam client, I entered the directory and ran a quick ls to figure out what I had to work with.

touma@setsuna:common/Trails in the Sky FC $ ls -la total 1986388 drwxr-xr-x 5 touma touma 4096 Oct 20 23:19 . drwxr-xr-x 10 touma touma 4096 Nov 5 20:43 .. drwxr-xr-x 2 touma touma 4096 Nov 5 2015 BGM drwxr-xr-x 4 touma touma 4096 Nov 5 2015 _CommonRedist -rwxr-xr-x 1 touma touma 787968 Feb 7 2016 Config.exe drwxr-xr-x 2 touma touma 4096 Nov 5 2015 dll -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 165311 Oct 20 20:08 dump -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 35621809 Feb 7 2016 ED6_DT00.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 18448 Feb 7 2016 ED6_DT00.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 2468101 Dec 16 2015 ED6_DT01.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 36880 Dec 16 2015 ED6_DT01.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 199759 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT02.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 9232 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT02.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 8696670 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT03.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 18448 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT03.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 18093622 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT04.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 9232 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT04.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 24291816 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT05.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT05.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 11260428 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT06.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 18448 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT06.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 66609144 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT07.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 72016 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT07.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 226823581 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT08.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT08.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 152468135 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT09.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 46096 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT09.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 222776216 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0A.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0A.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 121100311 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0B.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0B.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 26658261 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0C.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0C.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 6742488 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0D.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0D.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 91156 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0E.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 9232 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0E.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 1164468 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0F.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 9232 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT0F.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 221582 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT10.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 18448 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT10.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 189950 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT11.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 18448 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT11.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 441915 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT12.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT12.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 13191634 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT13.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT13.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 428173213 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT14.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT14.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 254700304 Nov 7 2015 ED6_DT15.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 7 2015 ED6_DT15.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 15105502 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT16.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT16.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 77669890 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT17.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 85893124 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT18.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 9011 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT19.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT19.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 47053132 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT1B.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 73708 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT1B.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 3992401 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT1C.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 18448 Nov 5 2015 ED6_DT1C.dir -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 581636 Nov 5 2015 ed6_logo.avi -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 176822844 Nov 5 2015 ed6_op.avi -rwxr-xr-x 1 touma touma 2019776 Feb 7 2016 ed6_win.exe -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 215120 Feb 7 2016 steam_api.dll -rw-r--r-- 1 touma touma 81768 Nov 27 2015 xinput1_3.dll

There’s a few interesting files in here for sure, but the one we’ll cover first off are the ED6_DTXX.(DAT|DIR) files as they’re the most interesting to us off a glance. Looking at the file size, it looks like these are probably archives for a bunch of game files. The DIR files also sound like a case of some kind of virtual filesystem.

For those who were not familiar for the reason this is done, it’s a very popular strategy in PC and console games. You can read a great answer on the Game Development Stack Exchange right here. To briefly summarize:

- Faster loading times since there’s less seek

- Full control of data, no OS

- Compression can be more effective, especially if data is packed tightly

A few Google queries reveals that the company who originally developed the game, FALCOM, has been known to use a specific archive format for a while and there are well known decompression programs available. Unfortunately, I was not be able to find much in the way of documentation. One of interest for us in particular is the “Falcom Data Archive Conversion Utility”, or just falcnvrt for short.

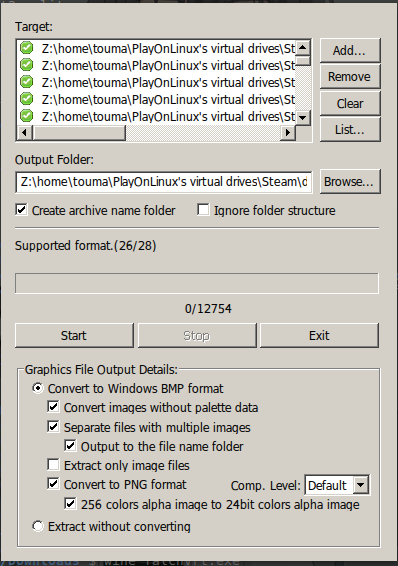

As it would turn out, this application can decompress the DAT files into directories:

If we go ahead and instruct it to encode them into PNGs for us, we will have them converted to a friendly format. This is because as it turns out, Falcom uses a custom raster bitmap format that isn’t readable by standard programs. Since we’re mostly interested in data right now and not the raster format, we’ll skip over how this is done and just chalk it up to the good work of the community.

With that, let’s dive deep…

Locating some sprites and their metadata

Let’s take a look at what we would get from unpacking:

touma@setsuna:~/unpacked $ find . -name "*.png*" | grep -E -o "ED6_DT.." | sort | uniq ED6_DT06 ED6_DT07 ED6_DT09 ED6_DT20 ED6_DT23 ED6_DT24 ED6_DT25 ED6_DT26 ED6_DT27 ED6_DT29 ED6_DT2F ED6_DT33 ED6_DT35 ED6_DT36 ED6_DT3A ED6_DT3C

OK, looks like these are some PNGs in those directories for us to take a look at. If we poke around at some of these files, we’ll find

some interest things but what we can start with is ED6_DT07/CH00000.png which represents the sprite of our Heroine, Estelle. More importantly, there seems to be an accompanying file named aptly CH00000P.SCP

Let’s get some metrics on these files:

touma@setsuna:unpacked $ file CH00000.png CH00000.png: PNG image data, 256 x 16384, 8-bit/color RGBA, non-interlaced touma@setsuna:unpacked $ file CH00000._CH CH00000._CH: data touma@setsuna:unpacked $

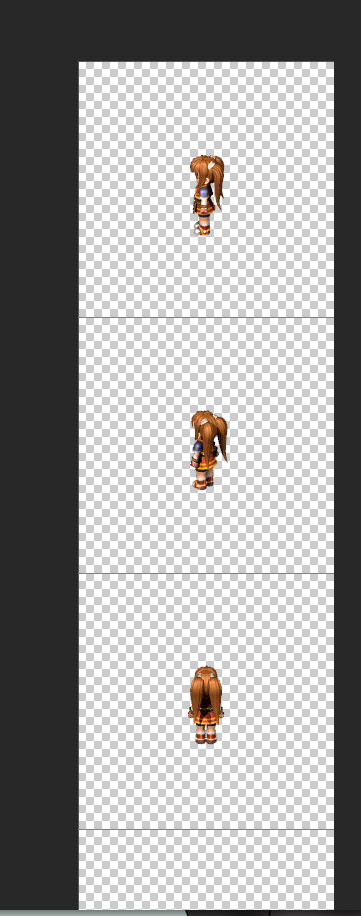

The latter is not very interesting but the former has some information to use in the way of sizing that would be informative to us. Using a little bit of knowledge of spritesheets we can guess that each frame is 256x256. This is because often in video games we use textures and sub textures that are powers of two and square because traditionally, GPUs can render these kinds of textures better and more efficiently. There’s no science to this guess then aside from some educated guesses.

Let’s verify this claim by loading it up into an image editor and setting some grids. I will be using Photoshop as it is a tool I am familiar with but you could really use anything that you have handy. By setting up sub-grids of 256x256 across the entire sprite sheet, we can visually determine if the spritesheet would have a high likelihood of satisfying our guess.

The above is done by using Photoshop “Grid & Slices” set to 256x256 to visualize the boundaries.

The above is done by using Photoshop “Grid & Slices” set to 256x256 to visualize the boundaries.

Yep, the frames seem to fit snuggly.

Before going forward, it helps to know characteristics of the file we are attacking and what we might look for. In the case of a sprite file, there are a few desirable characteristics that we should fine.

- A definition file will likely define the width and height of a frame if it’s not fixed

- The number of frames may be present somewhere in the file

- Timing and animation information may also be present

- Misc headers. which may / may not be useful to us

We can keep this in mind when examining the file.

Extracting metadata

OK, next up… let’s dump the metadata and see what we can gleam on first glance. Most files start with a header, so let’s begin there to see what we can see:

touma@setsuna:unpacked/ED6_DT07 $ hexdump CH00000P.SCP | head -n 4 0000000 0040 ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff 0000010 ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff * 00000b0 0000 0001 ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff ffff

OK, let’s keep in mind that list from before. I would expect a number of frames to be near the start of a file if it was going to be declared because it’s easy to read immediately and determine how many frame blocks in this file may potentially follow. 0x004 is interesting immediately because it is 64 in decimal – remember “16384” from the height? Pick your favourite calculator – I use the Python IDLE / REPL and compute 16384/256 … which is 64, which would make sense. So, our first 8-bit block here is clearly the number of frames (note: there is no rigorous proof for this – it’s an assumption I’ve made given the information available to me. Disassembly would be the only way to know for sure.)

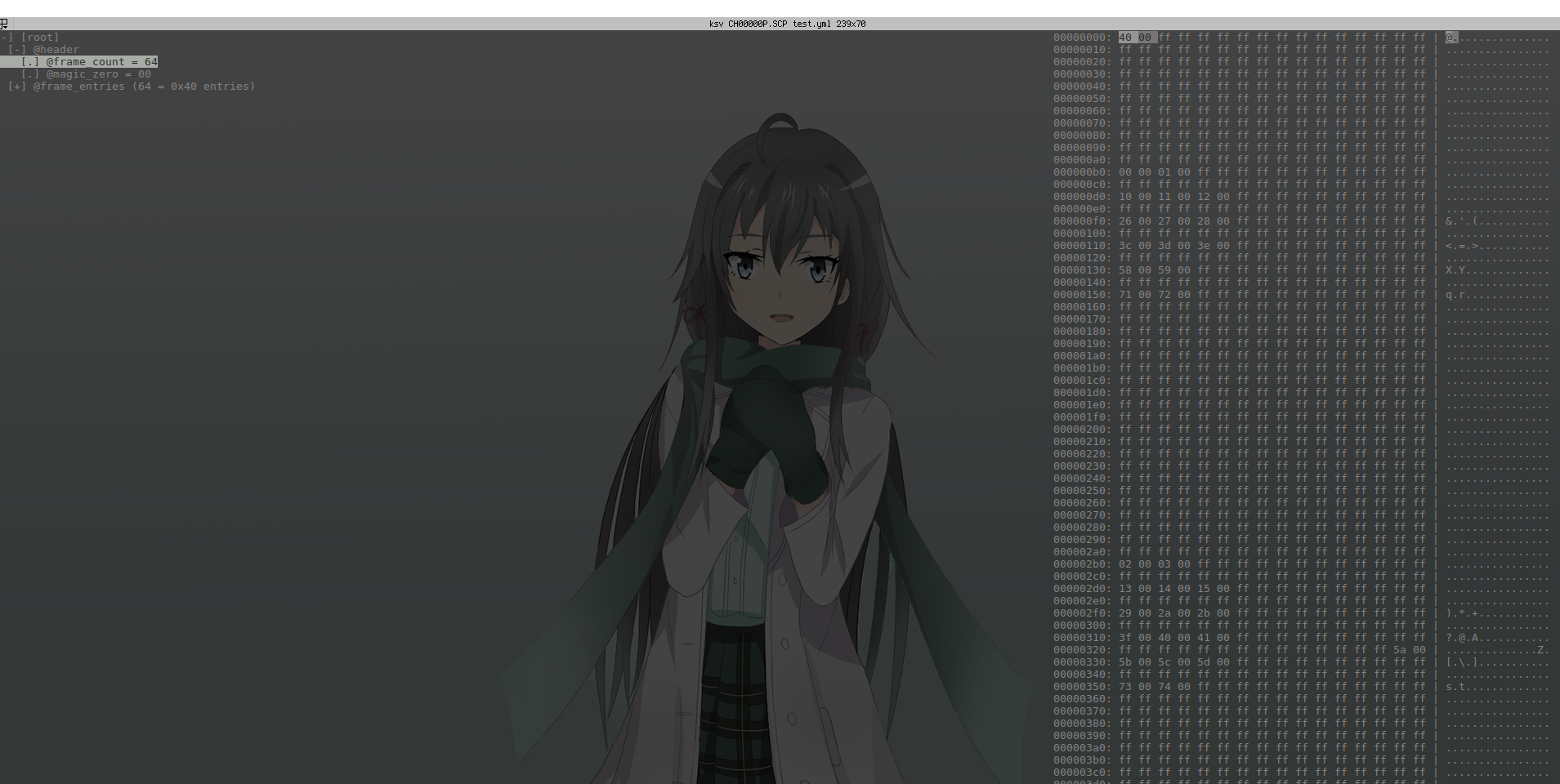

We should record this information. If you’re trying to follow along, you might consider installing Kaitai Struct now as I will be using it to browse data. However, you can record your notes in whatever you want – including markdown. I use Kaitai Struct because the visualizer allows me to view my assumptions and visualize the hexdump in a DSL that makes it easy to browse and test definitions. Then, when it comes time to import them into a programming language to manipulate, the compiler can take the DSL and generate an object definition for most major programming languages I use on a daily-basis. This makes it easy to interact with my new model.

You may also be interested in browsing the wiki here to be briefly familiar, though this is not required as all definitions are provided.

So, here’s what our notes will look like for the sprite.yml that we will create. This will be a definition file that is used by the Kaitai Struct Compiler and the Visualizer. By writing our notes and observations of the game data inside of Kaitai Struct, we gain the ability to visualize it quickly. For example, here is what we’re aiming to build here:

Note: Yukino in the background is my terminal background – not part of KSV

Note: Yukino in the background is my terminal background – not part of KSV

We can navigate a tree of data in semantic blocks that make sense to us rather than some homogeneous data blob. Yes, some hex editors have this ability but none of them are human readable like this and capable of generating object definitions from their DSL.

And you have to pay for a lot of them. So, what would a definition for this look like?

meta:

id: scp

application: TiTS Engine - Sprite Format

endian: le

seq:

- id: header

type: header

types:

header:

seq:

- id: frame_count

type: u1

- id: magic_zero

contents: [0]

How does this work? Meta is mostly describing ceremony. id and application are user-defined fields and do not affect parsing. Endianess is declared for how the bytes should be read. If you do not understand why we picked “le”, read the notes below and read up on Little Endian vs Big Endian.

After this, we really get into the meat of the definition. seq is declaring that are about to declare a bunch of sequential blocks from the current point in the file. Since this is the outter-most level of the YAML, it is the “root”. We declare something with the id of header, which is the name which will appear on object defintions and the visualizer, and the type. A type is analogous to a class or struct. It is a container and defintion for the block of data. In our case, we know for sure the file starts with some kind of header. It also probably contains some “frame data” as the screenshot before alluded to, so to make things easier to read we declare a type of header in the types below. Then, we just declare the nested seq block and we’re good to go.

With this, you would have the header portion of the above screenshot if you ran the following command:

ksv CH00000P.SCP sprite.yml

And you should see 64 listed as the frame_count. We could even compile with ksc now to get a working class but we don’t have anything worthwhile to compile just yet.

A couple of notes of other notes:

- We use Little-Endian here because this is an x86 processor game – which happen to use Little-Endian.

- We declared the frame_count as 8-bits and then some “magic zero” afterwards which we state is always zero. This very well could be some 16-bit number so that frame counts can exceed 2^8… but we’re not sure on that yet without looking at more files so we play this safe.

Then, there’s the rest of these huge blocks of data. If we load this into a hex editor or just use hexdump we see a lot of FF indicating empty space in the file. It would be unlikely for a header be padded with a huge amount of FF so we can assume that perhaps the header is just 2 bytes long. Hm… looks like no frame height or width information? It seems unlikely that it’s encoded here.

If we run find . -name "*.png*" | xargs file {} we’ll notice a lot of 256 wide PNG files. Actually, all of them in this folder seem to be like this. Furthermore, if we run our ksv tool and markup against some of these SCP files all their frame counts seem to match the heights, for example a small output:

./CH01593.png: PNG image data, 256 x 2048, 8-bit/color RGBA, non-interlaced ./CH00435.png: PNG image data, 256 x 8192, 8-bit/color RGBA, non-interlaced ./CH01033.png: PNG image data, 256 x 2048, 8-bit/color RGBA, non-interlaced ./CH02280.png: PNG image data, 256 x 16384, 8-bit/color RGBA, non-interlaced ./CH02130.png: PNG image data, 256 x 16384, 8-bit/color RGBA, non-interlaced ./CH00128.png: PNG image data, 256 x 14848, 8-bit/color RGBA, non-interlaced ...

OK, probably safe to assume that this data is hard-coded into the game engine somewhere and not stored here. Or it’s stored somewhere else.

That leaves us with a large file with some sparse data, though. When you see a lot of sparse data like this, you should think fixed length records … and I bet some frame data is encoded in these records. However, we should verify that this seems plausible and where it starts and ends.

stat the file to get a size and get started. i.e: stat CH00000P.SCP to get a size of 32770, in bytes. Now, it’s time to think.. if there was a record for each frame, how big would each record have to be? (32770-2)/64 in this case (remember: we sliced off two bytes for the header) which is a nice, round, 512. Remember CH01593 above? If we stat this file we get 4098… if we use the same logic then we get (4098-2)/8 = 512. It’s likely, but maybe not completely true, that we are looking at 512 byte records if we follow this train of thought. Let’s draft it out in Kaitai Struct and see what it would look like:

meta:

id: scp

application: TiTS Engine - Sprite Format

endian: le

seq:

- id: header

type: header

- id: frame_entries

type: frame_entries

repeat: eos

types:

header:

seq:

- id: frame_count

type: u1

- id: magic_zero

contents: [0]

frame_entries:

seq:

- id: junk

size: 174

- id: data1

type: u1

repeat: expr

repeat-expr: 4

- id: junk2

size: 334

A couple new syntax elements here. The most important in my opinion is the repeat: eos which is just saying create frame_entries until the file ends. This makes sense since we asserted that after the header, it would be all frame data. I have filled in some junk and data fields which might not make sense right now but they will once we load things up in ksv. I arrived at these offsets through dumping and examination but it will be more obvious where they come from once you load it up…

ksv CH00000P.SCP sprite.yml

Huh. Do you notice incrementing sequence of numbers in each block that are the same “offsets” apart? There’s a bunch of increasing sequences in the data actually if you look at it through the visualizer like this. The visualizer is really handy in letting you scope your search to what you believe to be localized data. I wonder what those could be for… :) On first glance, it feels like they could frame numbers or some kind of counters. Considering they’re the only data in here, one would have to imagine that perhaps they layout the sequence of the frames when played back. There’s a lot of possibilities – to figure it out, we will need to do one of two things:

- Once again, consider the characteristics of this file and what we think it might contain

- Disassemble the executable and read the resulting ASM code to how a loading routine for this file would marshal data around

When reverse engineering, it is a good idea to examine other test subjects time to time as well to verify claims. In this case, if we run ksv against CH01593P.SCP we’ll actually realize that “data1” is full of FF. Doh! And there are sequential clusters as well again but they do not start from 0 like the other definition. To learn more, we should study the makeup of each spritesheet and image how it would need to jump from frame to frame to be able to visualize this properly.

However, this post is getting pretty long as it stands, however, so we will wrap things up here. I wanted to provide a practical way of reverse-engineering data structures in Trails in the Sky using UNIX tools and Kaitai Struct and for that, I think I have succeeded. In the future, we may load these sheets up into an image editor to examine what is different and similar between them and their data files. (Hint: Things that move in all four directions like a PC Avatar are represented the same but different than say, a spell animation which flows in one linear sequence rather than jumping around in one of four directions like a PC Sprite.)

For a follow-up, would you prefer to see us reason this out again with more UNIX tools or an attempt to attack this file with static analysis by disassembly? Let me know in the comments – or feel free to just leave feedback or questions.