Automating adding missing require statements for globals using jscodeshift

Sometimes, working on some older legacy codebases they are using some Frankenstein build systems they created in house or a port to something like gulp, especially in some older open source projects. As part of getting them over to something else and to make use of new tech. such as “module bundlers”, part of the challenge is to make sure all imports are valid and dependencies are clear. Unfortunately, in some of these projects this is not made clear and it’s hard to tell.

Generally, you would add require or import statements to let developers know you are importing some code for usage. In some cases, the system is setup with some kind of loader already such as RequireJS and it’s just being used improperly. For example, take the following pieces of code:

class A extends Backbone.View {

render() {

this.$el.html(_.random(0, 10)) // set the view to something between 0-10

return this;

}

}

This has a dependency on something like lodash … or maybe underscore. If the code base just uses one, then it’s fine to be able to just import it and move on, if you know what it is. In this case, this is a lodash function.

So, what if we have hundreds of files like this? We can analyze the source code and make good guesses.

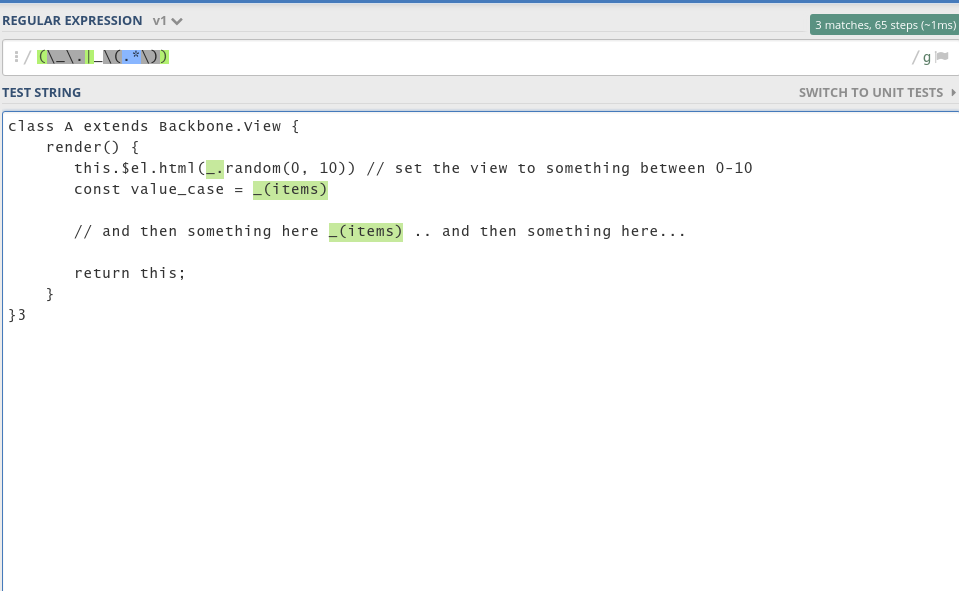

Use a regular expression to search the source code, then add them…?

If we were going for quick and easy, we might be tempted to use a regular expression. This would work but for things like lodash which uses _, there’s a few problems with that making it hard to identify when it’s actually in use:

- You could have something like

_(items)to wrap the entire collection for example, so you cannot just search for_. - .. but because of that, you can’t just search for

_either since you’re going to get way too many hits and next thing you know – every module depends on this! Might as well have just had aglobal.jsand had it declare it. - Even if you can write something to look out for the various forms, such as combing something like this:

… you immediately notice comments are a problem. You could probably add something to parse the line as well and make sure it’s not a comment. I share the same sentiment as Jeff Atwood:

I love regular expressions. No, I’m not sure you understand: I really love regular expressions.

… but that blog post summarizes what’s happening:

Some people, when confronted with a problem, think “I know, I’ll use regular expressions.” Now they have two problems.

Guess we should go fix them by hand, huh? Or should we charge on ahead? Or if you want, you play with the regular expression here first from above. Then do it for every single library… :(

If you eventually keep patching up cases, to succeed, you end up out of necessity with a parser. So, then…

Using a parser such as Babylon, esprima or other friends

You can read a lot more about projects such as Babylon and esprima as you would like but there’s just a couple things you need to know for this blog post:

- They parse a chunk of code into syntax elements that make sense for programatic consumption – this means being able to differentiate between say, a comment, an assignment (

const foo = bar()), statements (something) and just other things in Javascript land. - … and you can use

jscodeshiftplus one of the parsers to manipulate the Abstract Syntax Tree they produce in order to suit your needs using Javascript scripts.

So, let’s recap:

- We can find the difference between comments, statements, assignments, etc. This means we can tell apart a real usage of a token aside from a supposed usage.

- We can script it and programming languages are generally Turing Complete, where Regular Expressions are not. This means we can edit the AST as well, such as adding these require statements.

This is enough for us to be able to parse out what is being used. So, let’s get our hands dirty and figure out how to do this:

- Install

jscodeshift–npm install -g jscodeshiftif you usenpm - Write a transform to do this, and then run it against files in your code

How to get acquainted?

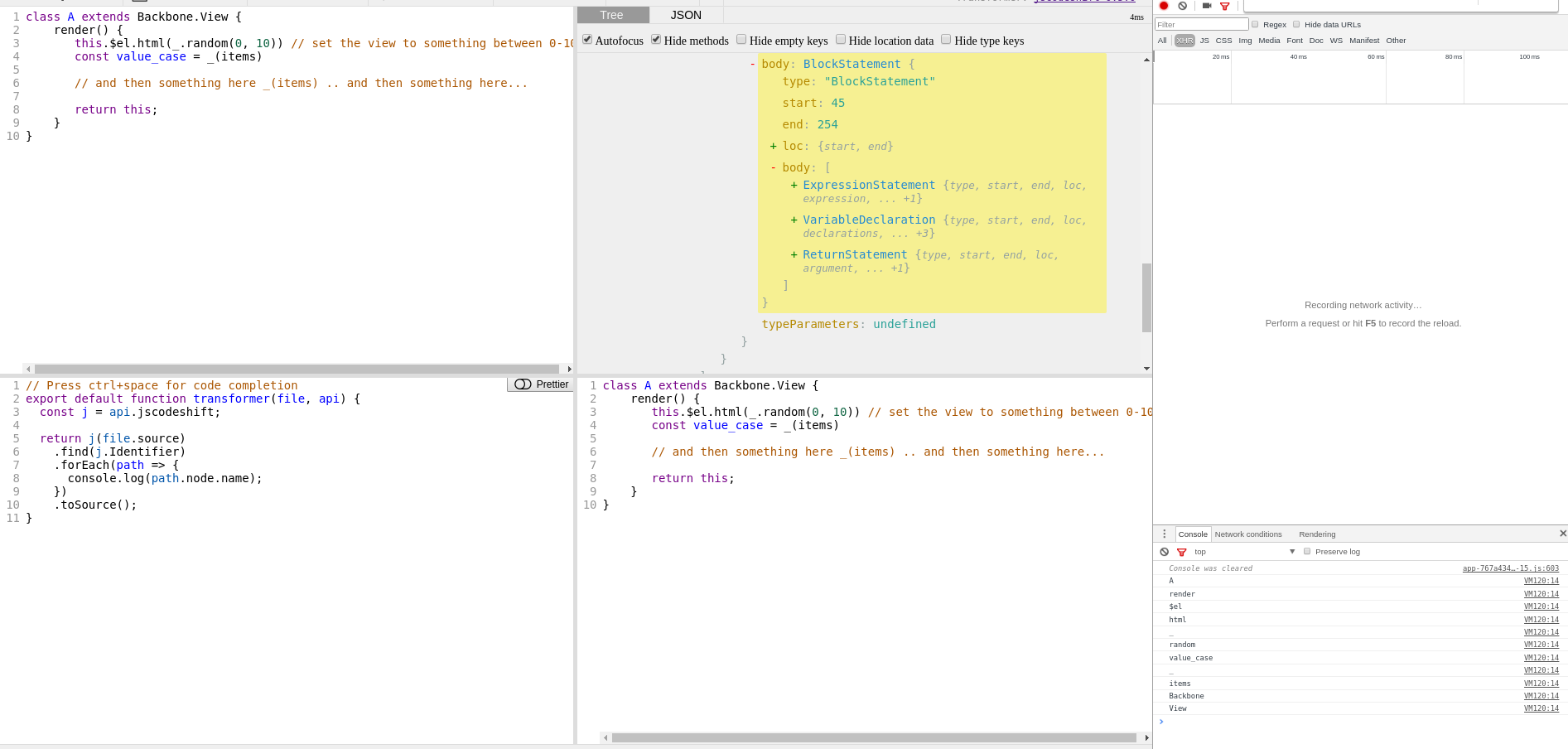

There’s a great site called ASTExplorer we’re going to use to get used to things. We’ll be using it to explore the code snippet from above. A couple housekeeping items…

- Make sure your language is set to “Javascript”

- Parser should be set to “Babylon” or something similar – since

jscodeshiftuses thebabelparser by default. - Transform tool should be set to

jscodeshift– that one should be obvious as to why.

If you load up your snippet code, then you should get something like this;

You will notice I have some code that logs out identifiers. First, let’s define what an identifier is and then let’s look at why we care about them.

What is an identifier?

Identifiers are value pairs / nodes that reference or define the name of a node. Often, they are the names of expressions, statements, class names, etc However, they are only for code. They have a couple important properties we care about:

- They don’t include any comments, which is undesirable for our case

- They’re entire words, separated by delimiters defined by the language syntax, making it easier to tell them apart, for example:

Backbone.Viewis tokenized into something like:BackboneView

- They can be boiled down into a list of identifiers that is nice and easy to iterate over and then map to statements.

So what about that output?

We get an output that looks something like:

A

VM120:14 render

VM120:14 $el

VM120:14 html

VM120:14 _

VM120:14 random

VM120:14 value_case

VM120:14 _

VM120:14 items

VM120:14 Backbone

VM120:14 View

For the sake of argument, we can say this output is exactly what we need, since it parsed out the _ and other identifiers we needed. If you add a comment with something else, like perhaps:

// $('div')

you will notice that nothing changes in the log changes. There are a couple flaws to this approach that aggressively would import more than require in some of the cases for some global tokens, but our goal is not perfect, just to get us most of the way there.

With token info in hand, there’s only one a couple things left to do. Let’s outline our plan of attack:

Creating a script to import something like lodash that was being used globally

We can start with something simple, given our previous input:

Input

class A extends Backbone.View {

render() {

this.$el.html(_.random(0, 10)) // set the view to something between 0-10

const value_case = _(items)

// and then something here _(items) .. and then something here...

// and then $

return this;

}

}

We want something like this:

_ - require('underscore');

class A extends Backbone.View {

render() {

this.$el.html(_.random(0, 10)) // set the view to something between 0-10

const value_case = _(items)

// and then something here _(items) .. and then something here...

// and then $

return this;

}

}

We will need a couple things here:

- A way of parsing out identifiers, which we already looked at.

- A way of injecting require statements into the code

- A way of checking if a require statement is already there, so we don’t duplicate it (this is optional – you can always run something like

rm-requiresafter to clean this up) - A way of outputting the source code

A way of parsing out identifiers, which we already looked at.

This is already complete – we looked at it above. We know how to load in a source code file and then loop over each identifier.

A way of injecting require statements into the code

There’s a few ways of doing this. There’s this package that promises you can do this. However, for something simple we can do something like this instead assuming we want them at the top of the file:

j(file.source).get().node.program.body.unshift(requireStatement)

This is basically getting the current file and then adding a line to the top.

Some ASTs might have something to do this with a specific node type, for example ts-simple-ast for TypeScript has this, but the parser we’re using does not for require statements, at least. After all, the only standardized module system is “ES2015 Modules” and if you were using those, you probably would not be in this problem.

A way of outputting the source code

This is built-in if you use the CLI tool – since it modifies files in place. You could also go to stdout as well, which is handy if you are doing dry runs. You just need to call toSource on the end of your fluent API.

Checking for duplicates

Since the above body variable from the injecting step is an array, we can just use includes

Plan of attack

That should be everything. Now:

- Iterate over all identifiers

- Finds one matching known problematic globals

- Inject a require statements, checking if it already exists

- .. and then terminate and print out the source code

Putting it all together, you get something like this

const containsStatementAlready = (builder, statement) => {

return builder.get().node.program.body.includes(statement);;

}

// Press ctrl+space for code completion

export default function transformer(file, api) {

const j = api.jscodeshift;

const builder = j(file.source);

return builder

.find(j.Identifier)

.forEach(path => {

const statement = "_ - require('underscore');";

if(path.node.name === '_' && !containsStatementAlready(builder, statement)) {

builder.get().node.program.body.unshift(statement);

}

})

.toSource();

}

With this, you get the output we wanted when run in ASTExplorer! Pretty simple and you can automate most of this, with some manual code review after to make sure things weren’t added in error. Don’t forget to save this as a index.js script and then use jscodeshift to run this against as a sample file locally as well – that’s where the real power comes and where you can dot this en-mass.

The best part of JSCodeShift is it’s just Javascript – so you’re scripting your automation. If wanted to, you can automate entire sets of globals using something as simple as a hash map (read: Javascript Object for simplicity) I’ll leave running this against your entire code-base (a zsh glob will probably do the trick…) and for multiple global tokens an exercise.

I actually did multiple tokens right here if you need something now.

I’m not sure this would be ready for a large project but it certainly should get you on the way. Most importantly, we learned a bit about what we can do with parsing an actual language that becomes a lot harder with something like a simple Regular Expression.

Where does this fail?

- There is going to be partial matches, for example:

_.$.retry- if this was a function, then we might (correctly) identify the identifier$but then mistakenly classify it as aglobal– even though it is not. These are safe in that they will justrequirein things that are not needed. - You might miss things if you’re not careful – for example, it possible to do something like

window['$']'and this is technically a string literal referring to the global. In practice, I find this is pretty rare so they can be solved by hand if required. However, we could definitely solve this problem with more code. This would become even harder to do with Regular Expressions – since context becomes so important and knowing the semantics of the language.

So, next time before you reach for a regular expression to solve a problem involving language rules – grab for a parser first instead, it might make your life a bit easier.